Entophile?

It has been a while since my last post on this blog. I don’t enjoy reading peoples’ complaints about not having kept up with their blog, but I feel like writing about it, so here we go.

There was a time when I identified as an entomologist. That was actually my official title at work, job series 0414 Entomologist. Granted I was working as a pest management consultant, and, lets face it, pest management is at the low end of respectability when it comes to entomology. But still, I could say that I was an entomologist, and people came me to with their pest questions. I was traveling to different military bases across the Pacific to train pesticide applicators and inspect pest management programs – it was a great time. Or should I say it was great for me. I had young children then, so it was not so great for my spouse who had to be a single parent while I was off having fun doing entomology. Looking back on it, I was selfish and maybe I’m the price now that my family is older and I am not as close with my kids as I could be, but maybe that is my emotionally detached personality. Regardless, it was a fun being an entomologist.

Eventually I saw that this was becoming a problem, so I changed positions. I was no longer a Navy pest management consultant and became a Navy natural resources manager. I have to admit there were some selfish motives for this change also. I saw an opportunity to get more into conservation, which I thought would be more rewarding. Also, I figured I would have more chances to get out in the field and do insect surveys, which was more exciting than pest management. This ended up being partially true, but the longer I was in that position, the more I got pushed into program administration. I suppose that is the natural progression of one’s career, but that didn’t make it any more palatable. I started out as the lone biologist in my new organization, and after about 8 years I was the team lead of a small group of biologists. I did manage get involved with some interesting projects, so it wasn’t all bad, but it got to the point where I wasn’t enjoying it anymore, and I was yearning for those days of traveling, helping people with pest problems, and training pesticide applicators on military bases throughout the Pacific.

It was another tough decision, but I made up my mind to get back to that place where I was happy and had that entophile identity. I decided to leave my natural resources position. When informed my supervisor, he told me that they were going to promote me and change my position to a higher grade. I was asked to reconsider, but in the end, I stuck with my decision and made the move back to my previous position. It was hard because we had built a good team, which I now realize is rare and not something to be taken for granted. My spouse also questioned the wisdom of passing up a promotion, but she was supportive and wanted what was best for me. The only problem was the entomologist in my previous position was not going to retire for another year, so I had to take a completely different position in the meantime. I ended up working in Range Sustainment, and by “range,” I mean military range used for training. This was not my area of expertise, but I figured I could do it until my old position opened up. I muddled through munitions and operational range clearance work for a little less than a year, but I was able to travel to Okinawa a couple times, so it wasn’t all bad.

Eventually the guy in my old position retired, and I was finally able to be an entomologist again. I was even in the same cubicle when I started almost 16 years earlier. The problem now was COVID. No one was in the office, and there was no travel. I was finally back to being an entomologist, but it was definitely not the same. I have to say though, I was still a lot happier, and I felt my old identity coming back.

Then my new supervisor got promoted, which left his position vacant. As luck (maybe bad luck, I don’t know) would have it, many of the folks on my new team were ineligible to fill the vacant supervisor position, and the ones that were eligible were not interested. I didn’t feel like it would be fair to my family for me to turn down a second promotion, and I didn’t want some random person to be my supervisor, so I took the new position.

So here I am now, feeling a little lost again. My new title is Supervisory Fish and Wildlife Biologist and it has been about one year. Our entire team is mostly teleworking full time and has been doing so since I started. I thought I could do entomology and be a supervisor at the same time, but that has not exactly worked out. I am now in the process of backfilling my previous position, and once that happens, I will be even more removed from entomology than I was before. It is OK though – I have accepted my role, and I understand that my first priority is trying to be a good supervisor, and of course it is nice making more money.

This gets back to my identity. Am I still an entophile? I’m still into bugs, but I don’t feel the same zeal. Maybe I am just out of practice. I do know that I want to start writing in this blog again, but I can’t say it is for certain going to be about insects all the time. Probably too late to change the name though.

Guam CRB Before and After Pics

The coconut rhinoceros beetle (CRB) was first detected on Guam at Tumon Bay in 2007. Despite eradication efforts, by 2010 CRB had spread island-wide. In 2013 a single CRB was found on Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam in a red palm weevil trap near Hickam Air Field which is jointly operated with Honolulu International Airport. I still vividly remember, as natural resources manager of the base, getting the call from my friend at the State Department of Agriculture just before Christmas and the craziness that ensued in the following months. That is a story worth telling some other time, but for now I just want to share some photos from Guam that show how destructive this invasive species and pest of palm trees can be.

In 2014 I had the awesome opportunity to attend the USGS Brown Tree Snake Rapid Response Training Course. It was one of the most fun things I’ve done in a long time. Perhaps it was because I don’t get the chance to go to Guam any more, or maybe it was just that I love searching for and catching snakes, but I really had a great time. I knew that CRB had hit Guam particularly hard, and also I knew that most folks in Hawaii don’t realize that we can potentially experience the similar impacts, so I decided the trip would be a good opportunity to get some photos of CRB damage. Furthermore, I thought it would be cool if I could find some pics on the internet of pre-CRB areas or early CRB areas with healthy coconut palms, then I could recreate the photos in 2014 to show how the trees had changed. It didn’t quite turn out as I had hoped, but here are the photos.

These photos are of the same section of coconut palms along the beach side of the War in the Pacific National Historic Park, Asan Beach. The top photo was taken by an unknown photographer in 2009 (can’t find it on the internet anymore so don’t know who to give credit to) and the bottom photo was my attempt to replicate the photo in 2014.

Images of palm trees again from the Asan Beach Ware in the Pacific National Historic Park, but they were taken in a different area. Top photo from the internet was taken in 2002 and bottom photo was recreated by me in 2014.

These photos were taken at the Agat Unit – Ga’an Point location of the War in the Pacific National Historic Park – the top was taken in 2013 and the bottom was recreated by me in 2014.

From these pictures alone the damage over the years does not seem to be catastrophic, although it does look like the trees overall area thinner and less full in 2014. There were some areas of the Asan Beach Memorial that were being hit very hard. The following are some pics of some of the CRB damage that was more obvious. These were all taken in 2014. I’ve got my fingers crossed that I will go back to Guam this year for BTS refresher training. If that is the case I hope to replicate these photos again.

Long view of Asan Beach War Memorial Park. See photos below with corresponding numbers in captions for close ups of tree damage.

Photo 1. Notched fronds are characteristic of CRB damage..

Picture 2. More damaged fronds.

Photo 3.

Photo 4.

Photo 5.

Photo 6.

Photo 7.

Photo 8.

Photo 9. This area was actually fence off because it was unsafe. Some of these palms were damaged so much they have died and may fall over.

Photo 10.

What is a “Good Entomologist?”

Recently there was an article in ESA’s Entomology Today about the habits of a successful entomologist (Ten Habits of Highly Successful Entomologists). I’ve actually pondered this question before. It never fails that whenever I’m chatting with colleagues and other bug folk of entomological origin, we start reminiscing on mutual acquaintances. When this happens there is always someone that is referred to as being a “good entomologist.” For example, it goes something like “Hey did you hear about Julie? Yeah, she got David’s old job at the State Department of Ag. Yeah, she’s a good entomologist.” Or maybe “Wow, did you hear about Randy? He got lost doing field work and had to eat his fly bait for a few days. He’s a little crazy, but he’s an awesome entomologist.” What does that really mean? Why do some people frequently get those props and others not so much? (full disclosure – I am in the latter category).

Getting back to the Ten Habits article, I have to say I was a little disappointed. I mean, it was a good story and I agree with all those habits, but they apply to any profession. If you do those things you’re going to be good at whatever you’ve chosen to do. Meditation, exercise, relationships, organization, etc., yes, all those things are great, but what specifically makes your peers consider you to be a good entomologist? Not even necessarily peers, but what prompts the uninitiated layperson to heap entomological praise on someone?

For me, it is simple. A good entomologist is someone who, when called upon at any time and in any circumstance, can make an insect ID to species from memory. We all know these people, and usually they have more to share than just the species name. A “good entomologist” can recite the biology of the specimen, and the really great ones will continue to talk for 30 minutes about it.

Mediocre entomologists like me can usually pass for good entomologists with the average person. You just have to cite the family name or even the order (anything sounding important) and give a few basic facts and you’re usually good. Before you know it, they’ll give you a moniker like bug man or bug girl. Nothing wrong with this. I call myself “The Entophile,” LOL. However, it is the walking, talking catalogs of insect knowledge that I label “good entomologists.” If they are lacking certain social skills they can be a little annoying, but that doesn’t lessen their status when it comes to entomology. Most of the good entomologists I know are older, but there are some young ones too. I love being around good entomologists because I have great admiration for the incredible amount of information stored in their heads, and I secretly hope their smarts will rub off on me (and I just find them to be cool in an unconventional way).

No doubt there are entomology icons that don’t necessarily fit in this category and that have achieved amazing accomplishments. No disrespect to them. I simply think a good entomologist is someone who can whip out an impromptu ID of an obscure insect and instantly recall its natural history like its no big deal. Way to go Bug Girl!

At the Congress

After a long break I’ve decided to start trying to write in my blog again. Not sure exactly where I came off the rails, but I need to start to doing some creative things again. Unfortunately it has been so long since I’ve done this that I don’t really remember how to post in WordPress anymore, so I am just going to start simple and see what happens.

I had the great fortune last weekend and this week to attend a couple days of the IUCN World Congress held in Honolulu. As usual my employer registered me at the very last moment so I didn’t realize that I had to sign up in advance for many of the workshops. The National Geographic Storytelling Workshop was really the main thing I wanted to go to, but I couldn’t get in.

The sting of getting shut of by Nat Geo was lessened a little bit when I happened to almost cross paths with E.O. Wilson…

E.O. Wilson sighting

E.O. Wilson macro shot

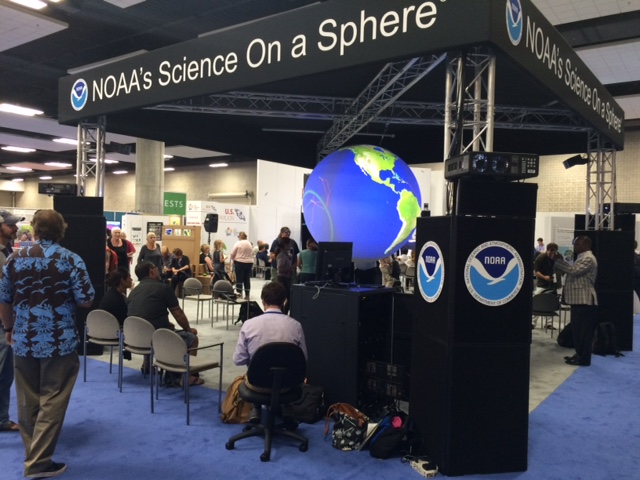

Since I couldn’t get into the workshops I spent most of my time in the exhibit hall, which was kind of fun since I was able to chat with a few friends and catch up with some folks I don’t normally get to see. Here are few shots from the exhibit hall…

One of the many presentations going on in the exhibit hall.

The seating and partitions were all made out of recyclable cardboard.

Google demonstration area.

NOAA Science on Sphere.

Hello Mr. Monk Seal.

So this was actually on the second floor, but it had a cool vibe. A hang out spot sponsored by National Geographic.

“I’d like to thank the IUCN for the opportunity to speak today…”

I took my family to the exhibit hall on Saturday and my kids had a good time (that is not my daughter in orange shirt). There was a mural for participants to paint something they thought was good for the earth.

My daughters painted the blue butterfly in the center – I suppose it is a lycaenid of some sort or maybe a blue morpho.

Feather-legged fly, Trichopoda pennipes (Diptera: Tachinidae)

A few weeks ago I was secretly checking out my neighbors invasive looking vine (which I now believe to be Thunbergia grandiflora or blue trumpet vine) when I noticed this unusual looking fly with with an orange abdomen and what appeared to be coreid style leaf feet. I ran in and grabbed my camera and was able to get a few pics, but could never get it to look directly at me – also was worried that my neighbor might get a little suspicious.

I did a little internet sleuthing and found a Hawaiian Ent Soc reference stating: “Trichopoda pennipes pilipes Fabricius was introduced into Hawaii from Trinidad in 1962 to combat the southern green stink bug, Nezara viridula (Fabricius) (Davis and Krauss, 1963; Davis, 1964).”

I did a little internet sleuthing and found a Hawaiian Ent Soc reference stating: “Trichopoda pennipes pilipes Fabricius was introduced into Hawaii from Trinidad in 1962 to combat the southern green stink bug, Nezara viridula (Fabricius) (Davis and Krauss, 1963; Davis, 1964).”

Unfortunately it parasitizes some other bugs as well…”In Hawaii, T. p. pilipes has been reared from the scutellerid Coleotichus blackburni White and the pentatomids Thyanta accera (McAtee) and Plautia stali Scott, in addition to N. viridula.”

The Bishop Museum’s Hawaii Biological Survey site says this in regard to the Koa Bug and T. pennipes:

“Unfortunately, a fly that was introduced to help get rid of the pest stink bugs (which have been causing problems with some of Hawaii’s agricultural crops) does not know the difference between the bad bug and the “good” koa bug. By going after the “wrong guy” it has had a impact on the reduction of its populations on most islands.

The koa bug is still around, but in very low numbers on most Hawaiian islands. There are only a few areas left on the Big Island where it is common. Hopefully our HBS field staff will find evidence on Maui that it is making a comeback.”

References:

Mohammad S. and J. W. Beardsley, Jr. 1975. Egg Viability and Larval Penetration in Trichopoda pennipes pilipes Fabricius (Diptera: Tachinidae). Proc. Hawaiian Entomol. Soc. 22: 133-136.

Ant Art

I discovered some more cool insect art today – I guess maybe you could call it “ant art.” Photographer/artist Andrey (Antrey) Pavlov from St Petersburg, Russia creates a window in into the secret life of the ants. Below are a few of my favorites, but you can find the gallery with the rest of his work here .

- “First Launch Ever” by Andrey Pavlov

- Статуя Труда (Statue of Labor) by Andrey Pavlov

- Extorters by Andrey Pavlov

- Reprisal by Andrey Pavlov

- Tili-Tili Dough by Andrey Pavlov

- Good Morning! by Andrey Pavlov

- жизнь прекрасна (Life is Beautiful) by Andrey Pavlov

A couple of weeks ago I was back up in Lualualei Valley checking on another species of Abutilon, Abutilon sandwicense. These plants were higher up in the mountains in a portion of the valley we refer to as the Halona Management Area. I don’t have much experience with Abutilon, but from the plants we have in Lualualei, A. sandwicense seems to grow much differently from A. menziesii – it grows tall and lanky, and it is not very bushy like menziesii. There were no flowers, but they seemed to be doing OK.

While I was there, I did some poking around on a nearby Sapindus tree that usually hides some nice little treasures. On the leaves I found Hyposmocoma, and, to my surprise, one appeared to have a parasitoid wasp lurking around its case. This same small tree also had some interesting Tetragnatha spiders, some cool Salticids (ant mimics?), and some kind of beetle larvae (I think?).

I had seen these Salticids on this same tree back in 2010, and at the time I inquiredabout them to the friendly entomologists at the Bishop Museum. I’m not sure he would want me quoting him, but in Frank Howarth’s words, “It’s a male Siler sp. [Salticidae] and apparently still undetermined. I’ve seen a specimen from Makua Valley. It was recorded from Hawaii by J. Proszynski 2002. (Remarks on Salticidae (Aranei) from Hawaii, with description of Havaika – gen. nov. Arthropoda Selecta ,vol. 10 (3): 225-241, f 81.) from a damaged specimen collected in 1974 by Wayne Gagne in the Waianae Mts.”

The Entomology staff at the Bishop Museum is awesome – Mahalo to Frank and Neal.

- Unknown beetle larvae

- Exuvium of unknown beetle larvae

- Tetragnatha sp.

- Tetragnatha sp.

- Tetragnatha sp.

- Salticidae (Siler sp.)

- Salticidae (Siler sp.)

- Hyposmocoma sp. with parasitoid

- Hyposmocoma sp. with parasitoid

- Hyposmocoma sp.

- Hyposmocoma sp.

- Sapindus oahuensis

- Abutilon sandwicense

Abutilon menziesii, Lualualei Valley

https://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/js/adsbygoogle.js?client=ca-pub-2837829364804164

There are two areas within the Navy Radio Telecommunications Facility and Munitions Storage Area where federally listed endangered Abutilon menziesii occur. Every month we go out and check on them, and this month they were flowering. I also noticed some interesting insect damage: feeding on the leaves, which I believe is from the Chinese Rose Beetle, Adoretus sinicus, a bore hole in a flower bud, and ants tending some kind of Homoptera (I didn’t collect any of the ants but they look like the white footed ant, Technomyrmex difficilis – not sure about the Homoptera either, at first I thought aphids but now I am thinking leafhoppers ).

- Ants on flower bud

- Ants tending Homoptera

- Ants tending Homoptera

- Ants tending Homoptera

- Damage to flower bud

- Leaf damage

- Abutilon menziesii, Lualualei Valley, Oahu, Hawaii

The tradewinds have been fairly strong lately, so this past Saturday I went for an early morning stroll along a beach a few minutes from where we live to see if I could find some Halobates. The genus Halobates consists of water striders (Gerridae) that live almost entirely in marine habitats and contains the only insect species living in the open ocean (The Marine Insect Halobates (Heteroptera: Gerridae): Biology, Adaptations, Distribution, and Phylogeney, Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review 2004, Nils Moller Andersen and Lanna Cheng 42:119–180).

Usually when the winds are strong you find these little guys on the windward side of Oahu hopping around in the sand, and I’ve always wanted to get some images of them, so I thought I would give it it a try. I also wanted to test out the macro abilities of my new camera. I recently bought a Canon Powershot SX30 IS – it wasn’t my first choice, but I couldn’t really justify getting a decent SLR and macro lens worth more than our minivan, so I had to make some compromises. I think it will work out OK for my purposes, and with a few accessories I should be able to get some decent insect macro shots. Having said that, it is still painfully obvious that the Canon 30D and 100 mm macro lens that I had access to at work were much better.

I did manage to find a few stranded striders hiding out in depressions in the sand. I’m not sure if these are H. hawaiiensis or H. sericeus. From what I’ve read, H. hawaiiensis is a near shore/coastal species and H. sericeus is an open ocean species, so I’m guessing that maybe these are H. sericeus that have been blown in with the trades, but that is only a guess (Biological Notes on the Pelagic Water Striders (Halobates) of the Hawaiian Islands, with Description of a New Species from Waikiki (Gerridae, Hemiptera), Proceedings of the Hawaiian Entomolgoical Society, 1938, Robert L. Usinger, 10:77-88).

- Halobates sp.

- Halobates sp.

- Halobates sp.

- Halobates sp.

- Halobates sp.

- Castle Beach, Kailua

Satan Antenna System

Earlier this year we conducted surveys for federally listed endangered Hawaiian Drosophila on land up in Kokee (Kauai) that the Navy manages. The sites are situated right against the critical habitat boundary, so we basically conduct our surveys along the fenclines and permiter of the property lines (this is the second year we have done these surveys). The last site in this area consists of a NASA facility with a giant antenna (access is prohibited, so there is a locked gate preventing unauthorized personnel from driving up to it). The big dish is pretty impressive, but I was more interested in the remnants of the previous antenna system that sit behind the current facility. There are some old footings and a small rusting blue structure labelled “Satan Antenna System”, complete with pitchfork logo. Evidently this stands for Satellite Automatic Tracking Antenna, and it dates back to the ’60s. While at the site, the remote feeling created by the combination of being in the middle of the forest and having an expansive view of the Pacific Ocean, together with standing in the shadow of a giant satellite dish that seemed to randomly come to life every 30 minutes and orient itself towards some unknown celestial target, tended to prompt the imagination to create images of what might be inside the little locked blue building…perhaps a long staircase into the darkness? Ernest Borgnine in a hooded robe?

Entophile Shop

Entophile Shop